I almost just wrote, "I had such a lovely weekend," but I can of course launch into describing (showing) instead of telling, and avoid the phrase altogether. I could then say, "I'm such a smartypants," but one would hope that my actions just showed that, rendering another phrase silly. Moving on (which I could also do without saying so. How do writers make up their minds?).

C was in for a visit, and it was our first time together since I visited her in Switzerland January 2004. Always very different in personality, we were both afraid that our friendship, originating in kindergarten, could not sustain the years we spent so far apart. Our concerns proved groundless.

Over three days, I took her around to my favorite haunts in Manhattan. A K-tour includes burning through some respectable shoe-leather, since I adore walking around the City and fixing my gaze on the delightful minutae that constitute "only in New York." I love peeking in the gate at Pomander Walk (nytimes has a history, written in 2000, of the alley here). I love to sit in Madison Square Park and watch the children, dogs, and business suited men on lunch breaks stroll through below the flatiron building. I love the fact that, within minutes, I can visit an Irish Hunger Memorial by the West Side Highway--C said it looked like the Shire, a DSW hidden in a movie theater, and Ground Zero. Man, I'm chock full o' love tonight.

On Saturday, another friend from high school, M, came in to visit. We met her in Union Square. The air felt properly autumnal, and we snacked on hot apple cider and ginger cookies from the farmer's market and watched New York pass by among the benches.

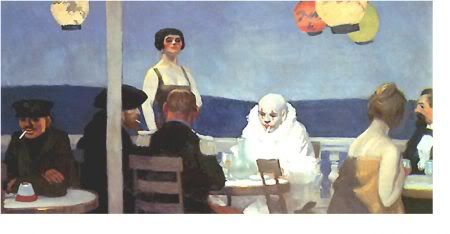

For dinner, we went to this restaurant at 53rd and 9th Ave that seemed to be the place for bachelorette parties (C said they're called "hen" parties in England. My feminist hackles shot up. Anna Quindlen recently wrote a stellar piece on feminism in Newsweek, which I may copy here after this to freshen the eyes). There was a large table of high school girls in the center who were having innocent fun, occasionally at the waiters' urging getting up on their chairs to boogie to the earsplitting, cheesy dance music. The bachelorette party next to us--not so innocent. The drunken bride-to-be, wearing a small mock veil, danced with a pudgy waiter's crotch whilst her friends snapped photos. Then the waiter lounged in a chair, and the spectacle ended with the bachelorette blushingly contemplating and then finally downing a shot which was covered in whipped cream and situated such that the act mimicked fellatio.

The three of us were rushed through our meal; multiple bigger parties, each with a member in a veil, milled on the sidewalk by the restaurant door.

* * * * * * * *

Anna Quindlen on feminism:

Not my writing, but something to which one might aspire, someday.Sept. 25, 2006 issue - I came to feminism the way some people come to social movements in their early years: out of self-interest. As a teenager, I was outspoken and outraged, which paired with a skirt was once considered arrogance. When I was expelled from convent school I was furious. Now I am more understanding. Would you have wanted to be the nun teaching me typing?

I got on the equality bandwagon because I was a young woman with a streak of ambition a mile wide, and without a change in the atmosphere I thought I was going to wind up living a life that would make me crazy. As my father said not long ago, "Can you imagine what it would have been like if you had been born 50 years earlier? Your life would have been miserable."

The great thing was that it was possible to do good for all while you were doing well for yourself. Each of us rose on the shoulders of women who had come before us. Move up, reach down: that was the motto of those who were worth knowing. But it was not just other women we elevated, but entire enterprises. More women on the staffs and the mastheads of the country's largest publications changed them. It resulted in newspapers and magazines that covered women as more than a amalgam of recipes and fashion collections. They simply became more reflective of the world around them, and therefore better.

I remember a page-one meeting in which I told my colleagues that it was fine if a story about Geraldine Ferraro recounted what she wore as long as her male Republican vice presidential opponent—George Bush I—got the same sartorial treatment. I envisioned daily tie dispatches: foulards, regimental stripes, embroidered Labradors and tiny tennis rackets. But I was conspicuously pregnant at the time, and no one really wanted to set me off; the references to the Ferraro skirt suit were deleted, leaving a bit of room for something of more substance. All in all, a very satisfactory day at the office.

There's one question that always lurks around the margins of the battle for equal rights: how will we know when we've won? Sometimes it seems like a classic dance of two steps forward, one back. Indra Nooyi, an Indian-born numbers cruncher, was recently named CEO of Pepsi. But that makes her one of only 11 women now running a Fortune 500 company, which works out to slightly more than 2 percent. CBS appointed the first woman solo network news anchor. But some genius Photoshopped a publicity still of Katie Couric even though Walter Cronkite had long ago made clear that a person with a normal face and physique can read a teleprompter. And Forbes magazine just published an essay titled "Don't Marry Career Women," by a male writer who couldn't see the advantages of a wife who could pay the mortgage and support the children even if her husband lost his job or suffered a massive coronary.

That kind of nonsense takes you back in time, to the early days when women dumped babies on the desk of the mayor of Syracuse to protest the lack of child care and picketed male-only press clubs. Maybe it was the classic protest slogan "Don't cook dinner—starve a rat today," but the perception was that the fight for equality was a war against men. But the battle was really against waste, the waste of talent, the waste to society, the waste of women who had certain gifts and goals and had to suppress both. The point was not to take over male terrain but to change it because it badly needed changing. The depth and breadth of that transformation is what reflects the success of the movement, and by that measure, women are doing well. And so is everyone else.

Fathers take a far larger role in the daily raising of their kids. Companies feel more pressure to be sensitive to medical and family emergencies. Sex crimes are prosecuted; so is domestic violence. Patients demand more personal care from their doctors. Readers want more human-interest stories from magazines. Even the bottom line has benefited. Catalyst, the research organization that tracks women at work, reported in 2004 that the Fortune 500 corporations with the most women in top positions yielded, on average, a 35 percent higher return on equity than those with the fewest female corporate officers.

When I was told 40 years ago that I should learn to type so I could someday type papers for my boyfriend, I didn't know what I wanted, but I knew it wasn't that. It's an act of hubris to think that things can be truly different, but hubris was what I had—hubris, and the millions of other women who knew that there must be more to life than waxy buildup and a frost-free freezer. In 1970, 46 women at this magazine charged it with workplace discrimination; today NEWSWEEK publishes an annual issue on women's leadership. That marks one of countless unremarked everyday distinctions between an old world and a better one, and, on a personal level, between a girl who would have been a mad housewife and a woman whose typing has been on her own terms.